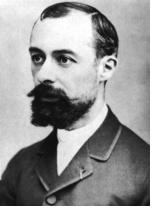

Antoine-Henri Becquerel

physicist, b. 15 December 1852 (Paris, France), d. 25 August 1908 (Le Croisic)

Henri Becquerel came from a family of professional scientists; his father, Alexander Edmond Becquerel, was a Professor of Applied Physics, his grandfather, Antoine César, had been a Fellow of the Royal Society, and his son Jean also became a physicist.

Henri Becquerel came from a family of professional scientists; his father, Alexander Edmond Becquerel, was a Professor of Applied Physics, his grandfather, Antoine César, had been a Fellow of the Royal Society, and his son Jean also became a physicist.

Becquerel studied at the École Polytechnique from 1872 to 1874 and the trained as an engineer at the École des Ponts et Chaussées (School of Bridges and Highways). He became an Engineer of the Department of Bridges and Highways in 1877 and was promoted to Ingénieur-en-chef in 1894.

In addition to his duties as a state's engineer Becquerel pursued a science career. In 1876 already he had obtained a position at the École Polytechnique. From 1878 he held an appointment as an assistant to his father, the Professor of Applied Physics at the National Museum of Natural History. In 1888 he acquired the degree of docteur-ès-sciences. On his father's death in 1892 Becquerel was appointed his successor in the Chair of Applied Physics. In 1895 finally he became a Professor at the École Polytechnique.

Like almost every physicist of his time Becquerel was interested in light, phosphorescence, magnetism and electricity phenomena. He studied infrared (heat) radiation, the spectra of phosphorescing crystals and phosphorescence emitted by some uranium compounds.

When Röntgen discovered X-rays and showed that they are accompanied by a type of phosphorescence in the vacuum tube, Becquerel decided to investigate whether there was any connection between X-rays and naturally occurring phosphorescence, known, for example, from uranium salts. He wrapped a photographic plate so that it was totally shielded from light, placed uranium salt crystals on top and exposed the arrangement to sunlight, thus exciting the crystals to phosphoresce. After several hours of exposure he found that the shielded plate after development showed silhouettes of the crystals. When he placed a metal coin between the crystals and the wrapped plate an image of the coin could be seen.

The phenomenon was found to be common to all uranium salts, and Becquerel concluded that it was a property of uranium. Soon after his first experiments he noticed that the same effect was observed when the salt crystals were placed on the wrapped plate without stimulation to phosphorescence by sunlight. Becquerel thought that this was some kind of invisible "metal phosphorescence." He reported his work to the Academy and in several papers in 1896 and 18997 but then turned again to other things.

What Becquerel had discovered was in fact natural radioactivity, ie. emission of rays similar but not identical to X-rays that cause the uranium atom to decay. The importance of this discovery was not appreciated until several years later when others discovered the same type of radiation in thorium, polonium and radium. Marie Curie then coined the name "radioactivity" for the phenomenon. In 1903 Becquerel was awarded half the Nobel Prize for Physics for his discovery, the other half being awarded to Pierre and Marie Curie. He was elected a member of the Académie des Sciences in 1889 and became Life Secretary of that body.

Once he understood the importance of his discovery Becquerel returned to the study of radiation. He performed experiments on beta radiation, a constituent of radioactivity, and showed that the beta particles are electrons. In 1901 he felt a burn from an active radium sample he had carried in his vest pocket. His report on the experience stimulated research into the medical uses of radioactivity.

References

Badash, L. (1995) Antoine-Henri Becquerel, Encyclopaedia Britannica 15th ed.

Nobel e-Museum, the Official Web Site of The Nobel Foundation (2004) Henri Becquerel. http://www.nobel.se/physics/laureates/1903/becquerel-bio.html (accessed 25 July 2004); based on Nobel Lectures. Physics 1901-1921, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1967.

home

Henri Becquerel came from a family of professional scientists; his father, Alexander Edmond Becquerel, was a Professor of Applied Physics, his grandfather, Antoine César, had been a Fellow of the Royal Society, and his son Jean also became a physicist.

Henri Becquerel came from a family of professional scientists; his father, Alexander Edmond Becquerel, was a Professor of Applied Physics, his grandfather, Antoine César, had been a Fellow of the Royal Society, and his son Jean also became a physicist.