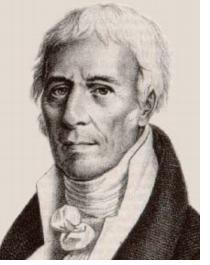

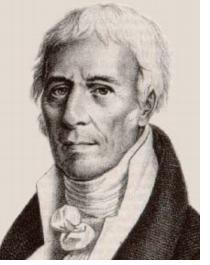

Jean-Baptiste(-Pierre-Antoine) de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck

Biologist, b. 1 August 1744 (Bazentin-le-Petit, Picardy, France), d. 18 December 1829 (Paris).

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck was the son of a baron and lieutenant of the infantry. His father sent him to a Jesuit school to prepare for the priesthood, but when his father died the 16 year old Lamarck joined an infantry regiment and served for seven years, first in a war against Germany and when peace was declared in 1763 at the Riviera.

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck was the son of a baron and lieutenant of the infantry. His father sent him to a Jesuit school to prepare for the priesthood, but when his father died the 16 year old Lamarck joined an infantry regiment and served for seven years, first in a war against Germany and when peace was declared in 1763 at the Riviera.

During his time with the army Lamarck developed an interest in plants. After his resignation he studied first medicine and then botany at the Jardon du Roi (Royal botanical gardens). He collected plants himself and studied for nine years before he published his Flore française ("French Flora") in three volumes in 1778.

News of new and strange plants from distant continents had raised the interest of the public in plants at home as well, and Lamarck's guide to the identification of plants, built on the principles of Linnaeus but not following him in every detail, became very popular. As a result Lamarck was elected a member of the Académie des Sciences and appointed as tutor to the son of the leading French naturalist Compte Georges de Buffon, with whom he undertook two years of travel to Europe's botanical gardens.

On is return to Paris Lamarck worked as curator for the royal herbarium and contributed articles to the Encyclopédie méthodique. When the revolutionary government closed the royal gardens in 1789 Lamarck proposed to the National Assembly that the random royal collection that had been assembled by amateur collectors be replaced by a scientific display, where all exhibits are shown according to their classification into classes, orders, etc to genera and species. He was a key figure in the development of the modern museum as a scientific institution. When the government established the Musée National d'Histoire Naturelle ("National Museum of Natural History") in 1793 Lamarck was appointed curator of invertebrates.

The first decade in that position led Lamarck into fruitless opposition to contemporary science. Lavoisier's discovery of the element as the basic building block of matter had allowed chemistry had discovered more and more elements, and biology was swamped by thousands of new plant and animal descriptions. Fearing that science would fall apart under the weight of empirical data without overarching concept, Lamarck conceived a plan for a series of publications that would unify physics, chemistry, geology, meteorology and the life sciences.

The first two volumes, entitled Recherche sur les causes des principaux faits physiques, et particulièrement sur celles de la combustion ("Research on the Causes of Principal Physical Facts, and Particularly on Those of Combustion"), appeared in 1794 and contained much speculation on matter and energy. They were followed in 1796 by Réfutation de la théorie pneumatique, ou de la nouvelle doctrine des chimistes modernes ("Refutation of the Pneumatic Theory, or of the New Doctrine of Modern Chemists"), a direct rejection of Lavoisier. It was probably in Lamarck's own interest as a scientist that none of these works was widely noticed; but he became disillusioned and embittered.

In 1801 Lamarck proved himself again as an eminent scientist with the publication of Système des animaux sans vertèbres, ou table général des classes ("System of Invertebrate Animals, or General Table of Classes"). Based on detailed anatomical study, this work established the basic arrangement of the invertebrates as it is still accepted in large parts today. His work Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres ("Natural History of Invertebrate Animals") showed him as the master of systematic museum collections.

Through his anatomical studies Lamarck had become aware of similarities and differences between different species and come to the conclusion that life evolves from simple forms to more complex creatures. This was a radically new idea; before Lamarck all creatures were believed to have been created simultaneously with all their differences.

Lamarck developed the idea in Recherches sur l'organisation des corps vivans ("Research on the Organization of Living Bodies") of 1802 and fully in his Philosophie zoologique ("Zoological Philosophy") of 1809. In the latter work he formulated two laws:

- Organs are improved by repeated use and weakened by disuse.

- The changes to organs so produced "are preserved by reproduction to the new individuals which arise."

While his first law is a statement of observation and can be easily verified, his second law postulates that changes to the body of a parent are inherited by the offspring. The idea of evolution through inheritance, later called Lamarckism, has been disproved by science. More importantly, though, Lamarck recognized the relationship between lifeforms and derived from it the necessity of evolution.

Lamarck's colleagues did not agree with evolution, and Lamarck was more and more isolated. He had to struggle with poverty, lost his eyesight in about 1808 and spent his last years cared for by his daughters. He received a poor man's funeral and was buried in a rented grave; after five years his body was removed, and no one now knows where his remains are.

The death notice in The Times paid no tribute to his considerable contributions to biology and conchology, concentrating instead on the politicking behind the search for his successor at the Jardin du Roi. Fraser's Magazine noted in their annual review of deaths that while Lamarck's name might have had some resonance in his heyday, his memory would soon be "consigned to oblivion". Fraser's had failed to notice that Lamarck's death in 1829 and included the notice in their December 1832 summary.

Reference

Ritterbush, D. C. (1995) Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck. Encyclopaedia Britannica 15th ed.

University of California San Diego, Mandeville Special Collections Library (1998), Weathering the Weather, The Origins of Atmospheric Science,

http://orpheus.ucsd.edu/speccoll/weather/lamarck.htm (accessed 18 April 2004)

Statue of Lamarck in the garden of the Musée National d'Histoire Naturelle

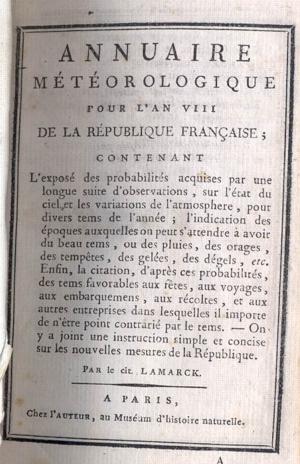

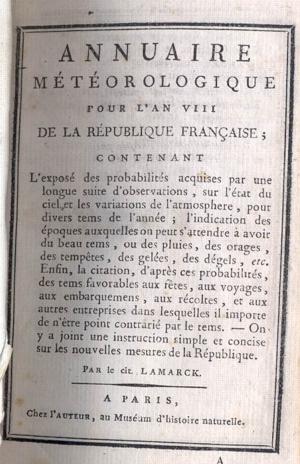

"Meteorological

Annual

for the year VIII*

of the French Republic;

containing

The description of probabilities established through a long suite of observations, on the state of the sky and the variations of the atmosphere, for different times of the year; the indication of periods for which one can expect to have good weather, or rain, storms, electrical storms, frost, snowmelt, etc. Finally, the identification, according to probabilities, of times favourable for festivities, travel, embarkations, harvests, and for other undertakings during which it is important not to be opposed by the weather. - A simple and concise instruction on the new measures of the Republic has been added.

By citizen Lamarck

at Paris,

published by the author, at the Museum of Natural History.

* year VIII of the Republic = 1800

home

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck was the son of a baron and lieutenant of the infantry. His father sent him to a Jesuit school to prepare for the priesthood, but when his father died the 16 year old Lamarck joined an infantry regiment and served for seven years, first in a war against Germany and when peace was declared in 1763 at the Riviera.

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck was the son of a baron and lieutenant of the infantry. His father sent him to a Jesuit school to prepare for the priesthood, but when his father died the 16 year old Lamarck joined an infantry regiment and served for seven years, first in a war against Germany and when peace was declared in 1763 at the Riviera.