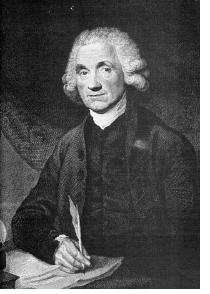

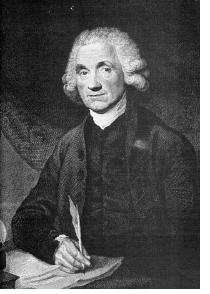

Joseph Priestley

Clergyman, political theorist and natural philosopher, b. 13 March 1733 (Birstall Fieldhead near Leeds, England), d. 6 February 1804 (Northumberland, Pennsylvania [today's USA]).

Priestley was born into a Calvinist family, but his father, a cloth dresser, wanted the young Joseph to prepare himself for the ministry in one of the other churches. Throughout his childhood Joseph was often sick and had ample time to spend on studies, which he did, mostly on his own.

Priestley was born into a Calvinist family, but his father, a cloth dresser, wanted the young Joseph to prepare himself for the ministry in one of the other churches. Throughout his childhood Joseph was often sick and had ample time to spend on studies, which he did, mostly on his own.

At 19, with somewhat improved health, Priestley entered a teaching institution established by the "Dissenting Churches" (Presbyterian and Independent), where he added the study of history, philosophy and science to his previous studies of Hebrew, Chaldee, Syriac and Arabic. He also set himself the task of translating every day 10 folio pages of Greek text.

As a result of his intense studies Priestley moved further and further away from Calvinism and other established church doctrines, without giving up his general adherence to a pious life. He became assistant minister in 1755 but had to change his congregation three years later, having been labelled a "furious freethinker."

In his new congregation he started a school in which he performed experiments with an air pump and a static electricity generator. He soon became known for his educational successes and was offered a tutor position at Warrington Academy, one of the few academic institutions open to members of Dissenting Churches.

Universities were reserved for Anglicans, so his students could only hope for a career in industry and commerce. Priestley began to write textbooks for the Academy with the career path of his students in mind. In a span of 5 years he published texts on history, science and the arts with an emphasis on practical applications. His Rudiments of English Grammar published in 1761 became the standard textbook for 50 years.

Priestley's work at the Warrington Academy transformed the institution into the most distinguished school of its kind in England, and the University of Edinburgh conferred on him a degree. In 1765 Priestley began to spend one month per year in London to meet leading scientists and discuss his experiments. As a result after a year he was elected a member of the Royal Society of London. In 1766 he published The History and Present State of Electricity, a work that contained several of his own discoveries and was translated into several languages.

Electical effects that occur during some chemical experiments drew Priestley towards chemistry. Throughout these years he remained in the service of the church, although a new appointment as minister in 1767 afforded him more time for experiments and writing. He now embarked on systematic work on gases. As a supporter of the phlogiston theory he adhered to the idea that matter consists of earth, fire, air and water; so he labelled the various gases he discovered different types of "air." Between 1767 and 1773 he discovered

- "nitrous air" (nitric oxide)

- "red nitrous vapour" (nitrogen dioxide)

- "diminished nitrous air" (nitrous oxide or "laughing gas"), and

- "marine acid air" (hydrogen chloride).

He introduced the technique of collecting gas above mercury, which allowed him to distinguish between water-soluble gases and those that were not water-soluble. His contribution "On Different Kinds of Air in the Philosophical Transactions of 1772 stimulated Lavoisier to develop a theoretical explanation. In 1774 he discovered what he called "dephlogisticated air" (oxygen), a feat for which he is generally remembered today. He was at that time employed as librarian and tutor for the sons of the 2nd earl of Shelbourne, who he accompanied later in the same year on a trip to Paris. This gave him an opportunity to meet Lavoisier and describe to him how he produced the dephlogisticated air.

Priestley kept discovering new gases but continued to adhere to the idea of different types of air against Lavoisier's new concept of elements. This did not deter him from making significant discoveries. He found, for example, that plant growth requires light (photosynthesis) and in the process produces dephlogisticated air (oxygen).

In 1779 Priestley established himself in Birmingham as an independent scientist, supported by a small annuity from the earl of Shelbourne and subscriptions raised by friends. In the Birmingham Lunar Society he discussed science with Erasmus Darwin the grandfather of Charles Darwin and famous naturalist, the steam engine engineer James Watt and the pottery manufacturer Josiah Wedgewood.

Besides his scientific work he began to write critical assessments of social developments. In 1769 he had already published his Essay on the First Principles of Government, and on the Nature of Political, Civil, and Religious Liberty, in which he expressed his belief in the power of reason and individual responsibility as the basis of society. His History of the Corruptions of Christianity of 1782, which rejected most fundamental tenets of Christianity and studied the Bible in its historical context, made his name known as an advocate of civil and religious liberty. When he openly supported the French Revolution his house, library and laboratory were destroyed during public violence in 1791 at the second anniversary of Bastille Day. Priestley tried to establish himself as a teacher in London, but the declaration of war against the French Revolution forced him to emigrate to North America in 1794. He was offered the chair of chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania but declined the offer.

Besides his scientific work he began to write critical assessments of social developments. In 1769 he had already published his Essay on the First Principles of Government, and on the Nature of Political, Civil, and Religious Liberty, in which he expressed his belief in the power of reason and individual responsibility as the basis of society. His History of the Corruptions of Christianity of 1782, which rejected most fundamental tenets of Christianity and studied the Bible in its historical context, made his name known as an advocate of civil and religious liberty. When he openly supported the French Revolution his house, library and laboratory were destroyed during public violence in 1791 at the second anniversary of Bastille Day. Priestley tried to establish himself as a teacher in London, but the declaration of war against the French Revolution forced him to emigrate to North America in 1794. He was offered the chair of chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania but declined the offer.

Scientific work proved difficult without easy contact with the European scientists. During the last decade of his life Priestley concentrated on religious activities. His work "A General History of the Christian Church " in four volumes was published between 1790 and 1803. His final work The Doctrines of Heathen Philosophy Compared with Those of Revelation appeared shortly after his death. He continues to be held in high regard as a scientist particularly in England today.

Reference

Ross, S. (1995) Joseph Priestley

. Encyclopaedia Britannica 15th ed.

The second, corrected edition of Priestley's report on his experiments with air.

An illustration of the technique to collect gas above water or mercury and investigate its effect on living plants.

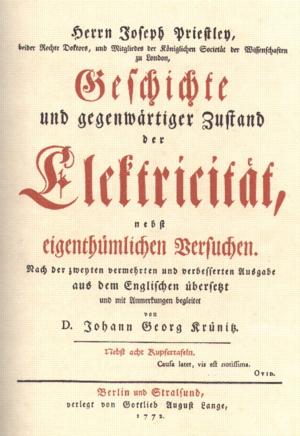

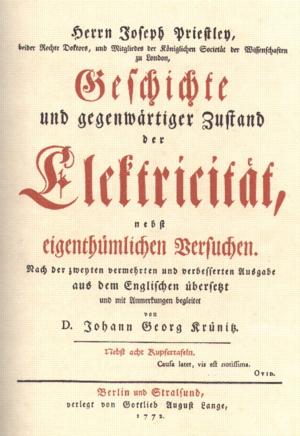

A German translation of Priestley's work The History and Present State of Electricity.

home

Priestley was born into a Calvinist family, but his father, a cloth dresser, wanted the young Joseph to prepare himself for the ministry in one of the other churches. Throughout his childhood Joseph was often sick and had ample time to spend on studies, which he did, mostly on his own.

Priestley was born into a Calvinist family, but his father, a cloth dresser, wanted the young Joseph to prepare himself for the ministry in one of the other churches. Throughout his childhood Joseph was often sick and had ample time to spend on studies, which he did, mostly on his own. Besides his scientific work he began to write critical assessments of social developments. In 1769 he had already published his Essay on the First Principles of Government, and on the Nature of Political, Civil, and Religious Liberty, in which he expressed his belief in the power of reason and individual responsibility as the basis of society. His History of the Corruptions of Christianity of 1782, which rejected most fundamental tenets of Christianity and studied the Bible in its historical context, made his name known as an advocate of civil and religious liberty. When he openly supported the French Revolution his house, library and laboratory were destroyed during public violence in 1791 at the second anniversary of Bastille Day. Priestley tried to establish himself as a teacher in London, but the declaration of war against the French Revolution forced him to emigrate to North America in 1794. He was offered the chair of chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania but declined the offer.

Besides his scientific work he began to write critical assessments of social developments. In 1769 he had already published his Essay on the First Principles of Government, and on the Nature of Political, Civil, and Religious Liberty, in which he expressed his belief in the power of reason and individual responsibility as the basis of society. His History of the Corruptions of Christianity of 1782, which rejected most fundamental tenets of Christianity and studied the Bible in its historical context, made his name known as an advocate of civil and religious liberty. When he openly supported the French Revolution his house, library and laboratory were destroyed during public violence in 1791 at the second anniversary of Bastille Day. Priestley tried to establish himself as a teacher in London, but the declaration of war against the French Revolution forced him to emigrate to North America in 1794. He was offered the chair of chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania but declined the offer.