Charles-Louis de Secondat belonged to an old aristocratic family that had been ennobled in the 16th century. His mother died when he was seven years old, and he inherited from her the title baron de la Brède.

Charles-Louis de Secondat belonged to an old aristocratic family that had been ennobled in the 16th century. His mother died when he was seven years old, and he inherited from her the title baron de la Brède.Political philospher and author, b. 18 January 1689 (Château La Brède near Bordeaux, France), d. 10 February 1755 (Paris).

Charles-Louis de Secondat belonged to an old aristocratic family that had been ennobled in the 16th century. His mother died when he was seven years old, and he inherited from her the title baron de la Brède.

Charles-Louis de Secondat belonged to an old aristocratic family that had been ennobled in the 16th century. His mother died when he was seven years old, and he inherited from her the title baron de la Brède.

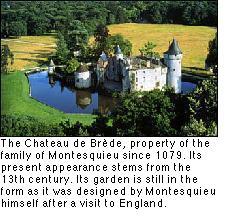

The young baron received a good education in the spirit of enlightenment and modern ideas. In 1705 he entered the University of Bordeaux, where he graduated in law three years later and established himself as an advocate. In 1713 he married Jeanne de Lartigue, who brought him a dowry of 100,000 livres. In 1716 his uncle, the baron de Montesquieu, died and left his title, his estates and the office of deputy president of the parliament of Bordeaux to Charles-Louis.

The 27 year old Montesquieu was now set up a wealthy man for life. His wit and intellect made him a welcome guest at all social occasions, and he could have led the idle life of his class. But Montesquieu had wider interests. He studied the sciences, particularly geology, biology and physics, and in 1721 published the Lettres persanes (Persian letters), a brilliant satire of French society and life in Paris.

His literary success encouraged Montesquieu to move to Paris and sell his position of deputy president of parliament. In 1728 he became a member of the Académie Française and decided to further his studies through travels. Leaving the management of his estates to his wife he visited Austria, Italy, Germany, Holland and England.

On his return to France Montesquieu settled at la Brède and concentrated on writing; but his Considérations sur les causes de la grandeur des Romains et de leur décadence ("Reflections on the Causes of the Grandeur and Declension of the Romans"), published in 1734, was the only work the public should see for two decades. Then, in 1748, Montesquieu surprised the world, who had thought of him as brilliant but superficial, with his masterpiece De l'esprit des loix (The Spirit of Laws). One of the most outstanding works on political theory, this work of 1,086 pages in 31 books is an all-encompassing study of the forms of government, the division of powers and the development of state organization under different climates.

On his return to France Montesquieu settled at la Brède and concentrated on writing; but his Considérations sur les causes de la grandeur des Romains et de leur décadence ("Reflections on the Causes of the Grandeur and Declension of the Romans"), published in 1734, was the only work the public should see for two decades. Then, in 1748, Montesquieu surprised the world, who had thought of him as brilliant but superficial, with his masterpiece De l'esprit des loix (The Spirit of Laws). One of the most outstanding works on political theory, this work of 1,086 pages in 31 books is an all-encompassing study of the forms of government, the division of powers and the development of state organization under different climates.

De l'esprit des loix established Montesquieu's fame in all of Europe. Philosophers said that he had discovered the laws of the intellectual world as Newton had discovered the laws of the physical world. Others considered it a danger to christianity. In 1750 Montesquieu defended his thoughts with the Défense de L'Esprit des loix, a work even more forceful and brilliant; but a year later the Catholic church placed De L'Esprit des loix on the list of forbidden books.

Underlying all of Montesquieu's works is a deep belief in human dignity. His modesty, kindness and preparedness to help others reflected this belief in his personal life. His ideas influenced the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Constitution of the United States of America, and he is one of the forefathers of the principle of Human Rights.

The editors of the Encyclopédie wanted Montesquieu to write on democarcy and despotism, but he replied that he had already said everything he had to say in his own work and would prefer to write a contribution on taste. The article Essai sur le goût ("Essai on Taste") was his last work.

Montesquieu's major works are:

Shackleton, R. (1995) Charles-Louis de Secondat, baron de la Brède et de Montesquieu. Encyclopaedia Britannica 15th ed.