David Hume

Scottish philosopher, historian and economist, b. 7 May (26 April*) 1711 (Edinburgh, Scotland), d. 25 August 1779 (Edinburgh).

David Hume came from an upper class family of modest income; his father, who died when David was three years old, was the owner of a small estate, his mother the daughter of the president of the Scottish law court. The young David went to university and was destined to study law. He found the subject not to his taste and began to read widely instead. He indulged in this pastime so without limits that he had a nervous breakdown at the age of 17 and did not recover for several years.

David Hume came from an upper class family of modest income; his father, who died when David was three years old, was the owner of a small estate, his mother the daughter of the president of the Scottish law court. The young David went to university and was destined to study law. He found the subject not to his taste and began to read widely instead. He indulged in this pastime so without limits that he had a nervous breakdown at the age of 17 and did not recover for several years.

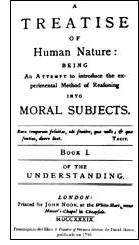

After a few months in a merchant's office the 23 year old Hume went to France, where he lived in the countryside and wrote A Treatise of Human Nature, his first major work. It consists of three parts

- Book I: On Understanding

- Book II: On Passion

- Book III: On Morals

This work is a thorough exposition of Hume's debate with the rise of science and Newton's laws of nature. Book I discusses the origin of ideas, the concepts of space and time and the testimony of the senses; book II develops a psychology of emotional and affective actions; book III describes moral goodness as a feeling of approval of human behaviour.

Books I and II were published in 1739, book III in the following year. They met with moderate success; Hume was accused of atheism, and his attempt in 1744 to be appointed to the chair of moral philosophy at the University of Edinburgh was unsuccessful.

The next seven years saw Hume support himself as a tutor in England and Italy. He used the time to rewrite the Treatise, which he considered rather juvenile. The Philosophical Essays Concerning Human Understanding of 1748 was a rewriting of Book I, the Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals of 1751 a rewriting of Book III. Their publication allowed Hume to return to Edinburgh, where he was appointed keeper of the Advocates' Library in 1752.

His new position gave him the time and opportunity to write and study. During 1754 - 1762 he published his History of England from its invasion by the Roman armies to 1688, a work that became the standard text for many decades. In 1757 he also rewrote Book II as one part of the Four Dissertations.

In 1763 Hume became secretary to the British embassy in France. He enjoyed life in Paris immensely and met the great French thinkers of the time. When he returned to England in 1766 he offered Rousseau refuge from persecution, but Rousseau, quite unjustifiably, suspected treason and secretly returned to France, where he painted Hume in a bad light. Hume was forced to publish their correspondence to prove his good intentions.

Hume spent the last years of his life in Edinburgh, Scotland, preparing new editions of his works and writing his autobiography.

Hume tried to use the scientific method of deriving laws from obeservations as the basis of his philosophical work and merged it with the methodology of Locke. He wanted to discover how the mind works when it acquires "knowledge". Starting out from "understanding" he distinguishes between the collection of data or sensations, which he calls "impressions," and "ideas," which are derived from such data in an attempt to make sense of them: There are no ideas without observations.

Hume then moves on to discuss causality and states that observations can never provide causality; causality is only in the realm of ideas. The inference of causal relationships can therefore be only a belief.

Hume's scepticism about the rigid connections between cause and effect stood in opposition to the new science of Newton (who he admired). His writings influenced philosphers for many decades. Immanuel Kant developed his philosophy in disputation with Hume's work. Adam Smith described his friend as "approaching as nearly to the idea of a perfectly wise and virtuous man as perhaps the nature of human frailty will permit."" The Catholic church saw it differently; it could not tolerate Hume's disbelief in life after death and placed his writings on its list of banned books. Among his major works are:

Philosophy and Religion

Philosophy and Religion

- A Treatise of Human Nature: Being an Attempt to Introduce the Experimental Method of Reasoning into Moral Subjects (1739-1740)

- An Abstract of a Book Lately Published: Entitled, A Treatise of Human Nature, etc., Wherein the Chief Argument of That Book Is Farther Illustrated and Explained (1740)

- Philosophical Essays Concerning Human Understanding (1748; many later editions entitled An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding)

- Four Dissertations (1757)

- Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779)

- A Letter from a Gentleman to His Friend Containing Some Observations on Religion and Morality (1745)

Politics and Morals

- Essays, Moral and Political (1741-1742)

- An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals (1751)

- Political Discourses (1752)

History

- The History of Great Britain (1754-1757)

- The History of England Under the House of Tudor (1759)

- Th History of England from the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the Accession of Henry VII (1762)

Autobiography

- A Concise and Genuine Account of the Dispute Between Mr. Hume and Mr. Rousseau (1766)

- The Life of David Hume, Esquire, Written by Himself (1777)

Reference

Jessop, T. E. and M. Cranston (1995) David Hume. Encyclopaedia Britannica 15th ed.

* Scottish date of the time. The calendar used in continental Europe did not come into force in England and Scotland until 1752.

home

David Hume came from an upper class family of modest income; his father, who died when David was three years old, was the owner of a small estate, his mother the daughter of the president of the Scottish law court. The young David went to university and was destined to study law. He found the subject not to his taste and began to read widely instead. He indulged in this pastime so without limits that he had a nervous breakdown at the age of 17 and did not recover for several years.

David Hume came from an upper class family of modest income; his father, who died when David was three years old, was the owner of a small estate, his mother the daughter of the president of the Scottish law court. The young David went to university and was destined to study law. He found the subject not to his taste and began to read widely instead. He indulged in this pastime so without limits that he had a nervous breakdown at the age of 17 and did not recover for several years. Philosophy and Religion

Philosophy and Religion