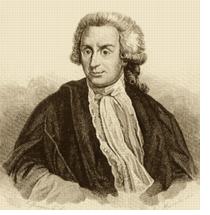

Luigi Galvani

Mathematician, physicist and philosopher, b. 9 September 1737 (Bologna, Papal States, Italy), d. 4 December 1798 (Bologna).

As a young man Luigi Galvani intended to study theology and enter a monastic order, but his parents persuaded him to turn to the sciences. Galvani entered the University of Bologna to study medicine. He obtained the doctoral degree in 1762 with a thesis De ossibus on the formation and development of bones and was appointed lecturer in anatomy at the university and professor of obstetrics at the Institute of Arts and Sciences. In 1772 he became president of the Academy of Sciences of Bologna.

As a young man Luigi Galvani intended to study theology and enter a monastic order, but his parents persuaded him to turn to the sciences. Galvani entered the University of Bologna to study medicine. He obtained the doctoral degree in 1762 with a thesis De ossibus on the formation and development of bones and was appointed lecturer in anatomy at the university and professor of obstetrics at the Institute of Arts and Sciences. In 1772 he became president of the Academy of Sciences of Bologna.

Galvani's research began with experiments in comparative anatomy and physiology and included a study of the kidneys of birds and of their sense of hearing and the anatomy of frogs. in 1780 an accidental observation of the twitching of the legs of a dissected frog when the bared crural nerve was touched with the steel scalpel, while sparks were passing from an electric machine nearby, made him focus on animal electricity, work that occupied him for the rest of his life and made him well known throughout Europe.

It was known at the time that something called "electricity" could be generated by friction and transmitted through metal. Through a series of experiments Galvani came to believe that some kind of electricity was generated in the tissue of the frog and activated the frog's muscles. He called this new type of electricity "animal electricity", as distinct from "artificial electricity" (static electricity generated by friction) and "natural electricity" (lightning). He believed that "animal electricity" was a fluid secreted by the brain, and proposed that flow of this fluid through the nerves activated the muscles.

After eleven years or experimentation Galvani published his ideas in 1791 in an essay, De Viribus Electicitatis in Motu Musculari Commentarius (Commentary on the Effect of Electricity on Muscular Motion). Although his explanation of muscular movement induced by electricity was wrong, most scientists accepted his ideas, and his work stimulated science into new lines of investigation, both in physiology and in electricity.

Alessandro Volta at the University of Padua was sceptical about Galvani's explanations, and the two scientists exchanged much correspondence, which stimulated Galvani into more experiments to defend his theory. Volta was convinced that the frog's legs acted as an electroscope (a device to indicate the flow of electricity) but that the electricity was generated outside the frog's body between two different metals.

(In hindsight, Galvani correctly attributed the observed muscular movement to electricity but was wrong in ascribing it to animal electricity, while Volta was correct in ascribing it to an outside cause but wrong in his statement that electro-physiological effects cannot occur without the presence of two different metals.)

Galvani grew tired of the controversy. In 1794 he wrote an anonymous defence of his position in Italian, Dell'uso e dell'attività dell'arco conduttore nella contrazione del muscoli (On the Use and Activity of the Conductive Arch in the Contraction of Muscles) and went on to concentrate on teaching and working as an obstetrician and surgeon, treating everyone who asked for help and set the fee according to the patients' ability to pay.

Galvani was a very religious man. He ended every lecture with an exhortation of "that eternal Providence, which develops, conserves, and circulates life among so many divers beings." His religious nature served him well while Bologna was a Papal state; but when Bologna became part of the secular Cisalpine Republic established by Napoleon in 1797 he refused to take the oath of allegiance and was dismissed from the university. He took refuge with his brother Giacomo and broke down completely through poverty and discouragement.

Galvani's friends managed to obtain an exemption from the oath for Galvani, and he could return to the university as professor emeritus. But the dismissal and subsequent ordeal had broken Galvani's spirit, and he died before his new appointment could come into effect.

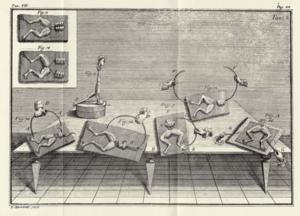

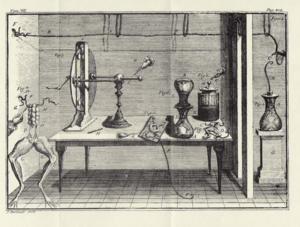

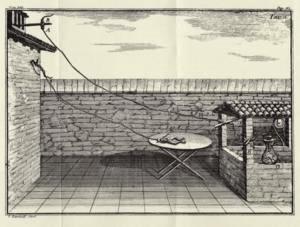

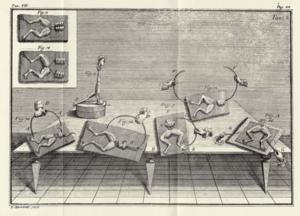

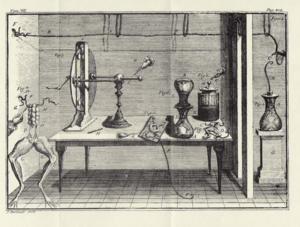

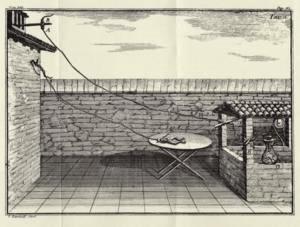

Selected illustrations from Galvani's works

The following illustrations show some of Galvani's illustrations from his work "Commentary on the Effect of Electricity on Muscular Motion" (MIT, 2004)

One of the principles of science is that experiments should be documented such that others can verify their result by repeating them. Galvani's illustrations are excellent examples of scientific documentation.

The last figure is an illustration of an experiment to investigate the effect of thunderstorms on muscle contraction. Galvani described his observations thus:

"Therefore having noticed that frog preparations which hung by copper hooks from the iron railings surrounding a balcony of our house contracted not only during thunder storms but also in fine weather, I decided to determine whether or not these contractions were due to the action of atmospheric electricity....Finally....I began to scrape and press the hook fastened to the back bone against the iron railing to see whether by such a procedure contractions might be excited, and whether instead of an alteration in the condition of the atmospheric electricity some other changes might be effective. I then noticed frequent contractions, none of which depended on the variations of the weather."

References

Dibner, B. (1995) Luigi Galvani. Encyclopaedia Britannica 15th ed.

MIT (2004) llustrations from "Commentary on the Effects of Electricity on Muscular Motion" by Luigi Galvani; plates. Massachusetts Insitute of Technology, Burndy Library, Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology,

http://dibinst.mit.edu/BURNDY/OnlinePubs/Galvani/Plates/Plates.htm (accessed 9 March 2004)

home

As a young man Luigi Galvani intended to study theology and enter a monastic order, but his parents persuaded him to turn to the sciences. Galvani entered the University of Bologna to study medicine. He obtained the doctoral degree in 1762 with a thesis De ossibus on the formation and development of bones and was appointed lecturer in anatomy at the university and professor of obstetrics at the Institute of Arts and Sciences. In 1772 he became president of the Academy of Sciences of Bologna.

As a young man Luigi Galvani intended to study theology and enter a monastic order, but his parents persuaded him to turn to the sciences. Galvani entered the University of Bologna to study medicine. He obtained the doctoral degree in 1762 with a thesis De ossibus on the formation and development of bones and was appointed lecturer in anatomy at the university and professor of obstetrics at the Institute of Arts and Sciences. In 1772 he became president of the Academy of Sciences of Bologna.