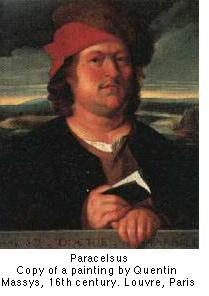

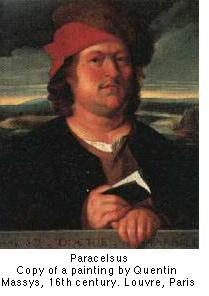

Paracelsus (Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim)

Physician and alchemist, b. 11 November or 17 December 1493 (Einsiedeln, Switzerland), d. 24 September 1541 (Salzburg, Austria).

Theophrastus von Hohenheim was the son of a German physician and chemist. His mother had died when Theophrastus was still a child. His father had then moved to Villach in Austria, where Theophrastus was trained in the Bergschule (Mountain School) as a chemist for one of the many gold, tin, mercury, iron and copper-sulfate mines of the region.

Theophrastus von Hohenheim was the son of a German physician and chemist. His mother had died when Theophrastus was still a child. His father had then moved to Villach in Austria, where Theophrastus was trained in the Bergschule (Mountain School) as a chemist for one of the many gold, tin, mercury, iron and copper-sulfate mines of the region.

When Theophrastus turned 14 he left home to study at a university. During the next five years he attended lectures at the universities of Basel, Tübingen, Vienna, Wittenberg, Leipzig, Heidelberg and Cologne. The standard of medical teaching, based as it was on Aristotle, Galen and Avicenna, did not impress him. "The universities do not teach all things," he wrote, "so a doctor must seek out old wives, gipsies, sorcerers, wandering tribes, old robbers, and such outlaws to take lessons from them. A doctor must be a traveller. ... Knowledge is experience."

And these were not empty words for Theophrastus. It is believed that he graduated from the University of Vienna at the age of 17, although he himself claimed to have obtained his degree from the University of Ferrara six years later. (The university records are missing for that year.) Medicine in Ferrara was critical of the classics and the prevailing view that the body and its functions are controlled by the stars and planets, which easily explains Theophrastus' preference for its university over Vienna. This was also the time when he adopted the name Paracelsus, thus indicating to the world that he considered himself "beyond Celsus."

Having obtained his degree, Paracelsus travelled through Europe, took on the position of army surgeon, was captures by the Tatars in Russia, escaped into Lithuania and became army surgeon again in Italy. He travelled through Egypt, Arabia and the Middle East and ended up in Constantinople, always on the lookout for new ideas in alchemy and "the latent forces of Nature." As a practicing physician he developed new cures for many illnesses, and when the 33 year old Paracelsus returned to Villach after ten years of travelling his fame secured him the position of town physician and lecturer in medicine at the University of Basel.

Only years before his appointment Luther had posted his 95 theses on the doors of his church. Following his radical example, in 1527 Paracelsus pinned an invitation to the public on the faculty notice board to attend his medical lectures, which were to be held not in Latin but in German. As his fame spread through Europe the number of his enemies grew as well, and within less than a year he had to flee Basel in the dark of night.

Without home and support for the next eight years, Paracelsus stayed with friends in various places. He used the opportunity to put together Die grosse Wunderartzney ("The Great Miracle Medicine"), a work that restored his fame immediately. He was sought after as a physician by ruling houses and received an appointment from the prince-archbishop of Salzburg. A wealthy citizen of the city, he died at the age of 48 under mysterious circumstances in the White Horse Inn.

Paracelsus came to medicine from alchemy. Although he carried much unsubstantiated baggage with him on his intellectual travels, his new insights into natural causes of afflictions were outstanding - and also the cause for his tempestuous relationship with the apothecary guild, which he accused to profit from deliberately complicated prescriptions. In 1530 he wrote an excellent clinical description of syphilis and described the careful dosage of mercury compounds for oral use as treatment, a prescription that predated similar treatment of the early 20th century by 500 years.

Paracelsus described the "miners' disease" (silicosis), then commonly believed to be the mountain spirits' punishment for sin, as the result of inhaling metal vapours. He anticipated homoeopathy be declaring that "what makes a man ill also cures him" and "all things are poison, and nothing is without poison. The amount alone decides that a thing is no poison." He explained goitre as the result of lead and other minerals in drinking water and developed many new remedies based on admixtures of mercury, sulfur, iron and copper sulfate.

Paracelsus also wrote extensively on religious themes and prepared commentaries to the gospels. This aspect of his work gave him regular printing bans, from which much of Paracelsus' work in the area of medicinal science suffered as well. Later generations acknowledge that Paracelsus contributed significantly to the foundations of psychiatry.

Reference

Hargave, J. G. (1995) Paracelsus. Encyclopaedia Britannica 15th ed.

Title page of Paracelsus' medical-chemical writings, published in Frankfurt in 1605.

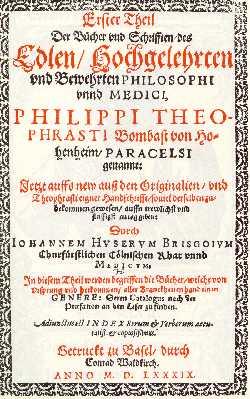

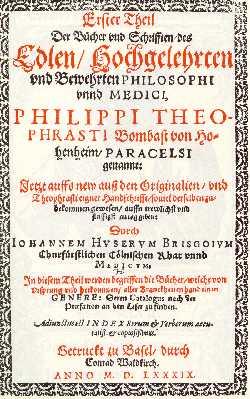

Title page of the complete non-theological works of Paracelsus in 10 volumes, published by John Huser in Basel during 1589 - 1590.

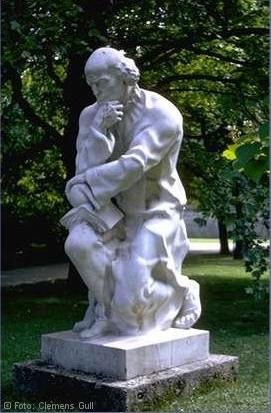

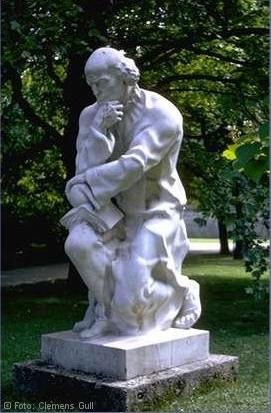

Memorial to Paracelsus in Salzburg.

home

Theophrastus von Hohenheim was the son of a German physician and chemist. His mother had died when Theophrastus was still a child. His father had then moved to Villach in Austria, where Theophrastus was trained in the Bergschule (Mountain School) as a chemist for one of the many gold, tin, mercury, iron and copper-sulfate mines of the region.

Theophrastus von Hohenheim was the son of a German physician and chemist. His mother had died when Theophrastus was still a child. His father had then moved to Villach in Austria, where Theophrastus was trained in the Bergschule (Mountain School) as a chemist for one of the many gold, tin, mercury, iron and copper-sulfate mines of the region.