Johannes Gutenberg

(Johann Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg)

German craftsman, inventor of the printing press with movable type, b. 1390/1400 (Mainz, Germany), d. 3 February (?) 1468 (Mainz).

Johannes Gutenberg, one of the greatest inventors of European civilization, was the son of a patrician of the city of Mainz in Germany. The patricians were involved in a lengthy and serious conflict with the professional guilds, and Johannes and his family had to emigrate to Strassbourg (then a German city) at some time around 1428 - 1430. Records show Gutenberg's presence there from 1443 to 1444.

Johannes Gutenberg, one of the greatest inventors of European civilization, was the son of a patrician of the city of Mainz in Germany. The patricians were involved in a lengthy and serious conflict with the professional guilds, and Johannes and his family had to emigrate to Strassbourg (then a German city) at some time around 1428 - 1430. Records show Gutenberg's presence there from 1443 to 1444.

Gutenberg had trained in various crafts and made his living from gem cutting and the training of apprentices. In his private hours he began work on an invention, which he tried to keep a secret from others. But his invention demanded investment, and Gutenberg's need for financial backing eventually forced him to disclose some details to his sponsors. In 1438 a five-year contract between him and three other men made the men partners in a venture to develop a printing press.

When one of the partners died in the same year, his heirs fought the close of the contract that stipulated that they could not become partners but were to be paid out. They lost the court case, but the trial brought several details into the public arena: Gutenberg had purchased a wooden press and - already in 1436 - a large amount of printing material.

Some time before 1448 Gutenberg returned to Mainz to borrow more money from relatives. By 1450 his invention had reached a stage where it promised returns, and Gutenberg could convince the financier Johann Fust to invest 800 guilders, for which the tools and equipment were given as security. Two years later Fust became a partner and invested another 800 guilders.

In about 1455 Gutenberg had completed his "42 Line Bible", the first printed book in European history. The sale of the print run would have probably been sufficient to pay out Fust and other creditors. But Gutenberg's desire for perfection and further improvement of the printing process apparently caused conflict with Fust, who wanted to see early and good returns. He took Gutenberg to court, supported by Gutenberg's assistant, Fust's son-in-law Peter Schöffer.

The court did not accept foreseeable income from the bible as assets. Gutenberg was ordered to pay Fust back his two sums plus compound interest without delay, and Fust and Schöffer started their own printing business, using Gutenberg's equipment and cast type. The Psalter, a magnificent work that had been prepared by Gutenberg and rivals the 42 Line Bible, appeared in 1457 with the names Fust and Schöffer as printers.

It appears likely that Gutenberg continued to run his own printing press despite this major setback; several early printed books are believed to be his work. It appears that after the masterpiece of the 42 Line bible he concentrated on products for more general use: Several school grammars are attributed to him, and in December 1454 he published the Türkenkalender, a calendar for the year 1455 with warnings against the consequences of the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453.

In 1465 the archbishop of Mainz granted Gutenberg a pension in the form of an annual supply of grain, wine and clothing and exemption from certain taxes. This indicates that Gutenberg did not receive wealth from his invention but did not starve during his last years.

Gutenberg's invention was a technical revolution with immense consequences. His printing process required a whole range of innovations, and Gutenberg mastered them all: the mould for the casting of the movable type in large numbers, the new metal alloy suitable for casting the type, the printing press adapted from existing wine presses, and the oil-based printing ink.

One of the first effects of Gutenberg's invention was the introduction of political, religious and philosophical tracts for wide distribution. The Reformatio Sigismundi is one of the first essays distributed in printed form.

Gutenberg's method of typesetting was in use virtually unchanged for six centuries. The introduction of computer typesetting during the second half of the 20th century will bring its demise.

Reference

Lehmann-Haupt, H. E. (1995) Johannes Gutenberg. Encyclopaedia Britannica 15th ed.

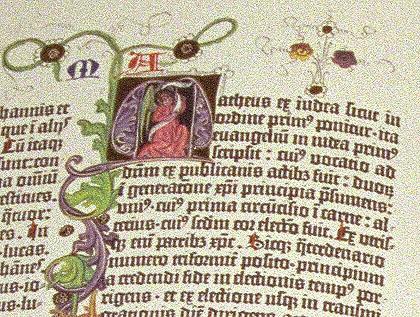

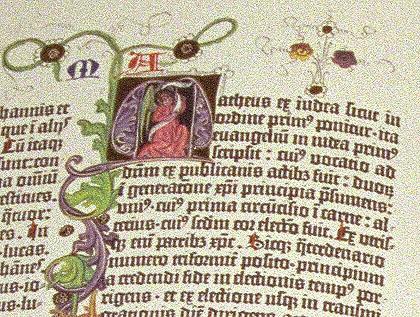

A page (from the gospel according to St. John) from the "Bible at 42 Lines", printed on vellum (a special quality parchment made from calve skin) in about 1455 on the Gutenberg printing press with hand-painted illustrations.

The 42 Line Bible is the first European book printed from movable type and the oldest complete book from the European civilization of which copies still exist. The number of copies for the print run is not known, but over 40 almost complete copies are still held in libraries around the world. The Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, the British Library in London and the Library of Congress in Washington all have complete copies.

In form the 42 Line Bible follows the layout of hand-copied manuscripts: It has no title page and no page numbers. But its technical qualities, the clarity of its Gothic font and the majestic appearance of its layout make it a work of art rarely surpassed by printed books during the next six centuries.

home

Johannes Gutenberg, one of the greatest inventors of European civilization, was the son of a patrician of the city of Mainz in Germany. The patricians were involved in a lengthy and serious conflict with the professional guilds, and Johannes and his family had to emigrate to Strassbourg (then a German city) at some time around 1428 - 1430. Records show Gutenberg's presence there from 1443 to 1444.

Johannes Gutenberg, one of the greatest inventors of European civilization, was the son of a patrician of the city of Mainz in Germany. The patricians were involved in a lengthy and serious conflict with the professional guilds, and Johannes and his family had to emigrate to Strassbourg (then a German city) at some time around 1428 - 1430. Records show Gutenberg's presence there from 1443 to 1444.