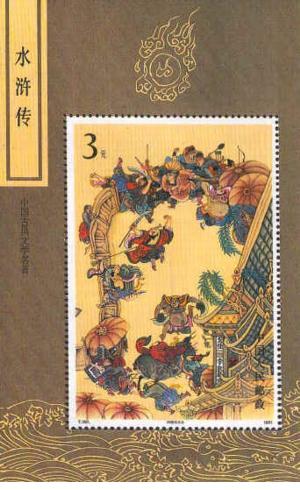

A scene from "Outlaws of the Marsh" on a Chinese postage stamp of 1991. |

Author of Shui Hu Zhuan ("Outlaws of the Marsh"), lived 13th or 14th century (Loh-yang, Honan, China).

Very little is known about Shi Nai'an. He almost certainly came from Loh-yang in Honan province and is generaaly believed to be the author, with a certain Luo Guanzhong, of Shui Hu Zhuan ("Outlaws of the Marsh"), one of the most popular novels of China.

If the remarks in the introductory chapter can be taken as a guide, Shi probably was a wealthy batchelor, who owned a country property and spent much of his time in the company of his friends. His statement that their discussions avoided all politics can probably be seen as an indication that political themes were their everyday fare - the contrast to the highly political content of Shui Hu Zhuan would be too stark otherwise.

Shui Hu Zhuan reports the life of Song Jiang of Shandong province, a lower official who was famed for his sense of justice and preparedness to help all in need - his readiness to support people in distress gave him the name "Timely Rain." Song Jiang is falsely accused of a crime and has to flee the city. His attempts to receive justice make matters worse, and eventually he becomes the leader of a large band of outlaws, who establish their fortified residence on Liangshan mountain, which is surrouded and secured by the vast Liangshan marshlands.

The story of Shui Hu Zhuan is based on fact; Song Jiang and many of his companions lived around 1100, and imperial records, which purposely avoid a mention of the "rebel" Song Jiang, report military operations against his troops shortly after 1120. It was a period of feudal despotism, and many officials suffered from injustice. Shui Hu Zhuan describes the intrigues of the courts and abuse of power in drastic images. Song and his outlaw generals fought to restore justice to those who suffered and to bring relief for the common people.

It is more than likely that the daring exploits and successes of the outlaws were part of general folklore well before Shi Nai'an put the story on paper. But he had a brilliant hand in painting the various characters as recognizable individuals through the entire story. Several women feature highly in the military and diplomatic exploits - sexual discrimination is forgotten where the pursuit of justice is the common aim.

Song's troops go from strength to strength through many battles, and although the many battle scenes may seem repetitive, the reader again and again derives satisfaction from the fact that the self-righteous imperial generals are defeated by an army of outlaws who fight for the right cause.

Shi's work was immediately popular and went through many editions. With its highly critical attitude to government officials and its exposure of corruption it was, of course, zensored more than once. An early edition of 70 chapters had no clear ending and left the outlaws' fate open to speculation.

Other editions had up to 124 chapters; all report that the imperial generals eventually recognized that the Liangshan mountain could not be taken. In an effort to neutralize Song, he and his troops received an imperial pardon in 1122 and were placed into imperial service to fight against the tatars in 1123. On his return from the successful military campaign, during which he lost most of his earlier generals, Song petitioned the emperor to be released to civilian duties. The emperor made him governor of Chuzhou, but envious imperial generals poisened him, and Song lives on as the ghost of the Liao Er flats.

Attemps to ban the book altogether occurred towards the end of the 17th century, when it was decreed that

The Liangshan marshlands have long been drained, but Shui Hu Zhuan continues to live. Its stories are known by all Chinese and most Japanese. Children can recount them, and they have been adapted for theatre performances and puppet shows.

A scene from "Outlaws of the Marsh" on a Chinese postage stamp of 1991. |