Li Shih-Chen (Li Shizhen)

Physician, b. 1518 (Waxiaopa, Huguang, China), d. 1593.

Li Shizhen was born in a small village on the Yellow River in today's Hubei Province. His grandfather had been an itinerant doctor (zoufang). Li's father Li Yenwen had followed him in the medical profession but could establish himself as a physician with a medical practice and attained the rank of a subordinate medical officer of the Imperial Medical Academy.

Li Shizhen was born in a small village on the Yellow River in today's Hubei Province. His grandfather had been an itinerant doctor (zoufang). Li's father Li Yenwen had followed him in the medical profession but could establish himself as a physician with a medical practice and attained the rank of a subordinate medical officer of the Imperial Medical Academy.

Li Yenwen wanted his son to advance in society and encouraged him to study for the imperial examinations and become a government official. Li Shih-Chen, who was more interested in his father's medical practice than government administration, passed the exams at county level when he was 14 but failed the national examinations three times.

At the age of 23 Li finally abandoned his studies of philosophy, law, and administrative procedures and with his father's support began serious studies of medicine. He became his father's assistant and during his free time read all available medical texts. He did not neglect general studies and in the Chinese tradition continued with philosophy and wrote poetry; but his main interest was the study of herbs and their use in prescriptions.

By the time Li was 27 years old he had already achieved wide recognition as a physician and was asked to diagnose the son of prince Zhu Xian of Chu. When his diagnosis was accurate he was appointed an official in the Chu Royal Court, in charge of the rituals and medical affairs. A few years later, he was recommended to the Imperial Medical Institute in Beijing as an assistant president.

But Li did not like life at the court and used his delicate health as an excuse to be relieved from his duties. He returned home and set up his own medical practice. He continued to consult all available books. The one year of service at the court had given him the access to rare books of the medical library, and Li began to notice obvious mistakes, wrong classifications and other serious errors.

Determined to bring order into the scattered medical knowledge of the time, Li decided to prepare an encyclopaedia. To find out what was correct and what was wrong and gather new information he travelled through China, talked to medical experts and collected specimen of plants, snakes, birds minerals and everything else of relevance. He visited places with large herb markets such as Anhui (still one of the largest herb trading centres today), Hunan, Jiangsu and Jiangshi and consulted some 800 books in medical libraries.

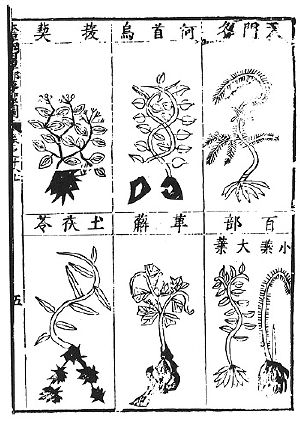

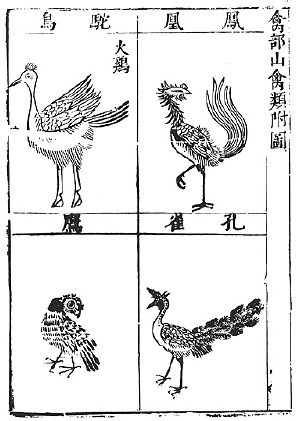

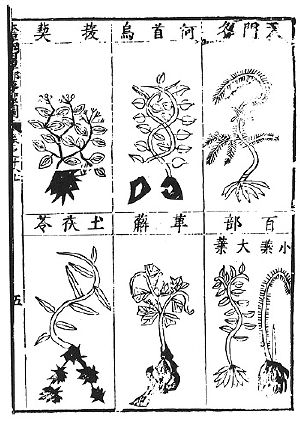

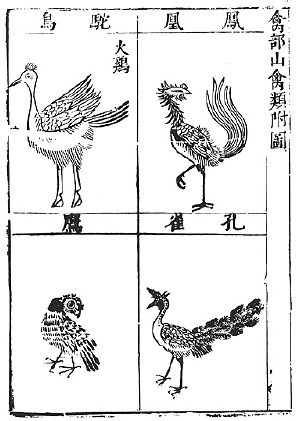

Li began his research when he was 30 years old. The first draft of Pen-ts'ao kang-mu (Bencao Gangmu , "Great Compendium of Herbs", also known as "Great Pharmacopoeia"), was ready in 1578 when Li was 60. Li revised it twice, in 1580 and in 1587. His sons and grandsons assisted with the final edition, which included many illustrations.

Li's son Li Qianyuan gave a copy to the imperial court to have it printed as a government work, but Emperor Wanli only added "Taken notice of; to be kept in the Ministry of Rites" to it, and the work disappeared from public view. It was eventually printed in 1596, three years after Li's death. A new edition of 1640 greatly improved the quality of the illustrations and added new drawings, making it 1,160 in total.

Li Shih-Chen was a true scientist of outstanding ability. His Pen-ts'ao kang-mu became the standard text for medicine; it was reprinted at least 15 times. Translations appeared into Japanese (abridged version in 1637; more complete version in 1783), Latin (1656), French (1735), English (1736 and 1741 by different British translators), Russian (1868) and German (1895).

The sheer size of the Pen-ts'ao kang-mu makes it the ultimate reference but also unwieldy for the general practitioner. Wang Ang (c. 1615-1700 ), an authority on herbal medicine, wrote about it:

- "From antiquity to the present time, several hundred authors have written Materia Medicas. None of them, however, surpasses the Bencao Gangmu of Li Shizhen in either spirit or accuracy. The examinations and studies are both profound and extensive; information is comprehensive and clear. For this reason, I admire the attitude of this man and would like to speak in praise of his extreme perfection. However, the chapters and volumes were written in such numbers that it is difficult to study completely during the course of a lifetime. Furthermore, it is rather cumbersome to bring along when travelling by boat or carriage. It is indeed an all-embracing work, but that which is essential cannot be recognized immediately. "

Commentaries on Li's work appeared within years of its publication. One major drawback was the lack of an index. It was rectified in 1652, when Cai Lixian published the Wanfang Zhenxian ("Needle and Thread for 10,000 Prescriptions") to assist users in finding herb formulas in the Pen-ts'ao kang-mu.

Reference

Subhuti Dharmananda (2003) Li Shizhen Scholar Worthy of Emulation

http://www.itmonline.org/arts/lishizhen.htm (accessed 26 November 2003)

Two illustrations from the edition of 1603:

home

Li Shizhen was born in a small village on the Yellow River in today's Hubei Province. His grandfather had been an itinerant doctor (zoufang). Li's father Li Yenwen had followed him in the medical profession but could establish himself as a physician with a medical practice and attained the rank of a subordinate medical officer of the Imperial Medical Academy.

Li Shizhen was born in a small village on the Yellow River in today's Hubei Province. His grandfather had been an itinerant doctor (zoufang). Li's father Li Yenwen had followed him in the medical profession but could establish himself as a physician with a medical practice and attained the rank of a subordinate medical officer of the Imperial Medical Academy.